Indirect searches for dark matter and signatures of physics beyond the Standard Model

1Shortcomings of the Standard Model¶

Observational facts: baryons at subdominant at most scales¶

Particle and nuclear physics allow us to understand the arrangement of observable matter in terms of baryons and leptons. Although the census of baryons seems to be consistent between estimates from big bang nucleosynthesis, CMB observations and probes of the intergalactic plasma (see Driver (2021)), the gravitational field arising from this baryonic matter does not seem to be strong enough, whether at the scale of galaxies, of galaxy clusters or even the cosmic microwave background.

Galactic scales¶

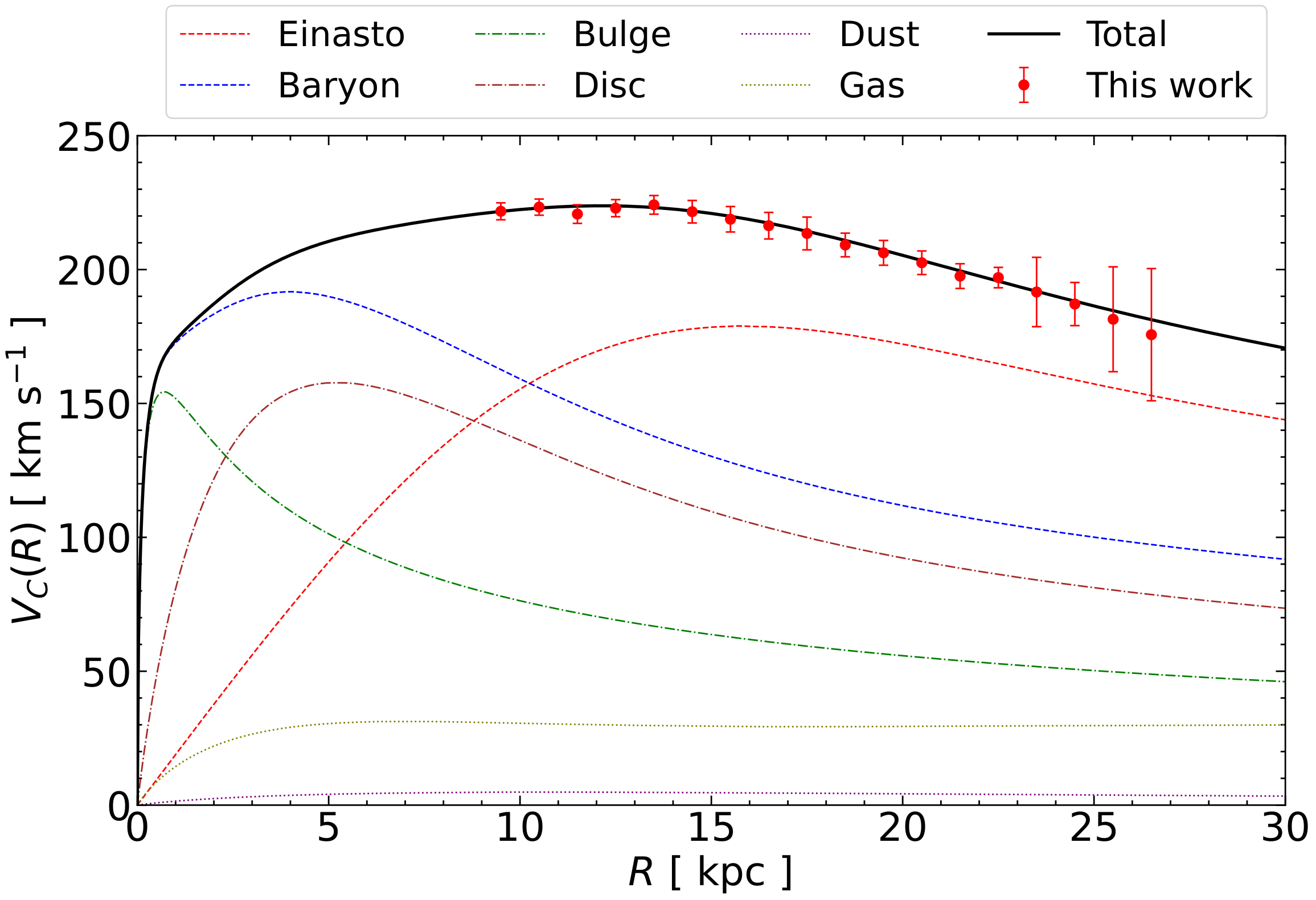

Kinematics is a fundamental tool for studying the distribution of matter in the universe. The distribution of the position and velocity of the stars in our Galaxy, measured by the Gaia satellite, can be used to reconstruct the rotation curve of the Milky Way, i.e. the rotation velocity of the stars as a function of their distance from Sgr A*, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:Rotation curve of the Milky Way, i.e. circular velocity as a function of distance to the center of the Milky Way. Extracted from Jiao et al. (2023).

Modelling this data provides an estimate of the total kinematic mass of the Milky Way of (Jiao et al. (2023)). This estimate seems reliable insofar as the Gaia data hints at the presence of a Keplerian decline, i.e. (for a circular orbit). Such a Keplerian decline is at odds with MOdified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) theories, which suggest a flat rotation curve at long distances. Despite this undeniable success in the field of stellar kinematics, it should be noted that the estimate of the total mass of the Milky Way remains uncertain: it could be up to times higher than the mass derived from stellar kinematics if one uses instead dwarf galacies orbiting the Milky Way (see discussion in Hunt & Vasiliev (2025)).

By comparison, the directly observable mass in our Galaxy, i.e. its stellar mass, represents only (Licquia & Newman (2015)) with an expected contribution from gas and dust of and , respectively. At least 70% of the mass of the Milky Way is dark (emitting no, or barely any, radiation).

In addition, modelling of the Gaia 6D data provides an estimate of the speed at which the Sun revolves around Sgr A*, i.e. as well as of the escape velocity from the Milky Way halo, i.e. (see Evans et al. (2018)). This relatively low escape velocity indicates that dark matter moves at low speed (): dark matter must be cold.

The local energy density of cold dark matter is inferred at , that is, for comparison, about 106 times the energy density of photon fields, magnetic fields or cosmic rays in the Milky Way.

Galaxy clusters¶

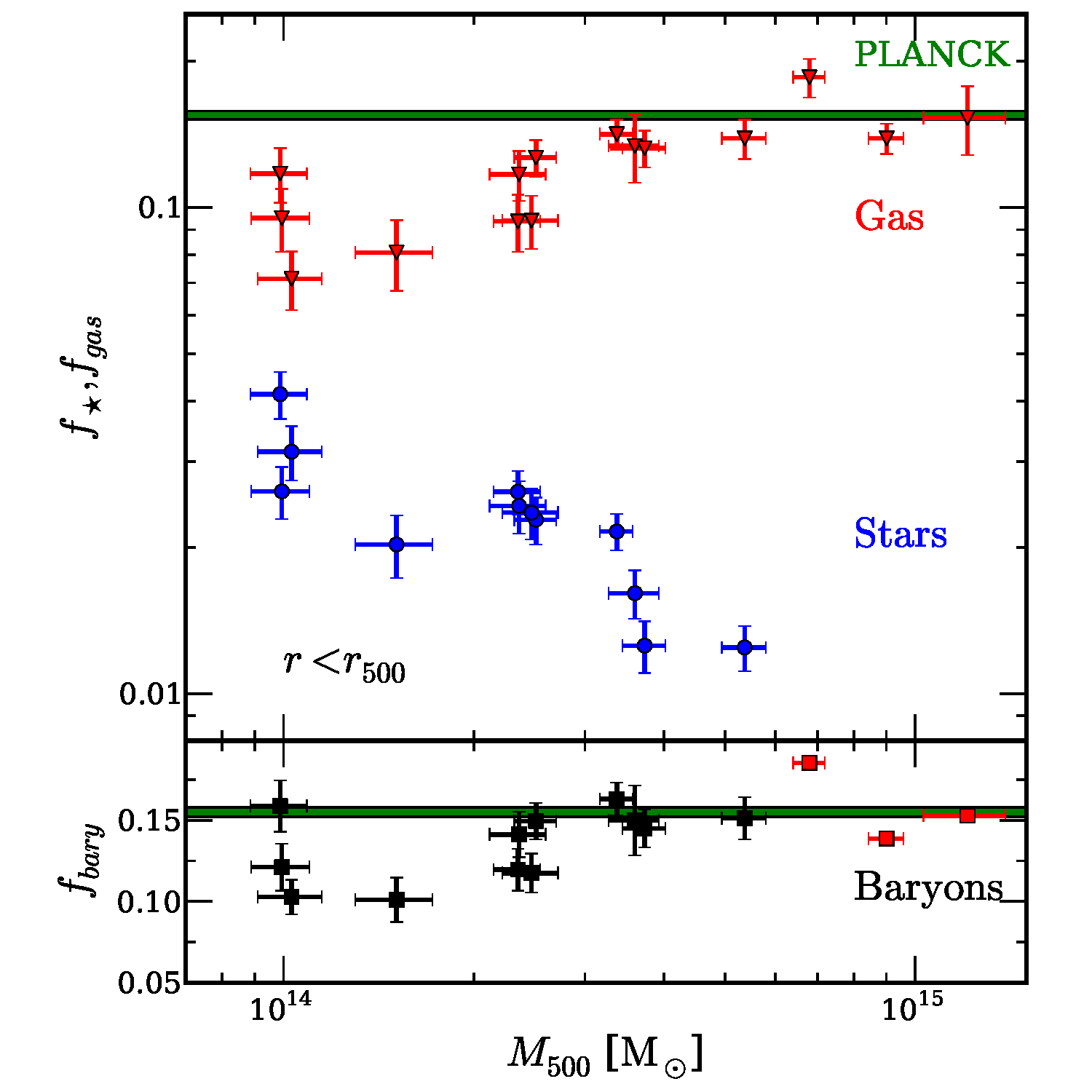

On a larger scale, galaxy clusters are the structures in the cosmic web whose matter distribution is best known (see e.g. Gonzalez et al. (2013)). Their gas content is estimated from their thermal Bremsstrahlung emission in X rays. Their stellar content is measured from their total near-infrared emission.

The total gravitational mass of galaxy clusters can be estimated by several methods:

- Lensing, if Einstein rings from a background source can be observed ;

- Virial theorem, applied to the galaxies in the cluster, i.e. , where and are the kinetic and potential energies respectively;

- Density and temperature profiles of the hot X-ray emitting gas, assuming hydrostatic equilibrium (self-gravity = internal pressure).

As shown in Figure 2, the sum of the stellar mass fraction and the gas mass fraction, i.e. the baryon fraction, is relatively independent of the total mass of the cluster: baryons contribute between 10% and 20% of the total mass in clusters.

Figure 2:Stellar, gas and baryon fraction as a function of total mass in a sample of 15 galaxy clusters. Extracted from Gonzalez et al. (2013).

CMB angular power spectrum¶

The CMB power spectrum is a powerful tool for determining the energy density of the various components when matter and radiation decoupled. A detailed discussion of the CMB spectrum is beyond the scope of this course. However, it should be noted that the amplitude of the fluctuations observed on angular scales ranging from a few arcminutes to a degree depends directly on the total matter density ( dark + baryonic mater), whereas the amplitude of the fluctuations on smaller angular scales depends on the baryon density. Detailed modelling of the CMB power spectrum measured with the Planck satellite (Planck Collaboration et al. (2020)) yields a ratio of the baryon energy density to the total matter density

Whether the universe is observed at the kpc scale (galaxies), the Mpc scale (galaxy clusters) or the Gpc scale (CMBs) , it appears that nearly of the mass needed to hold the various observed structures together is missing. The relative coherence of the baryonic fraction at all these scales leads to the hypothesis of the existence of cold dark matter, the nature of which is still unknown.

Notes on numerical approaches¶

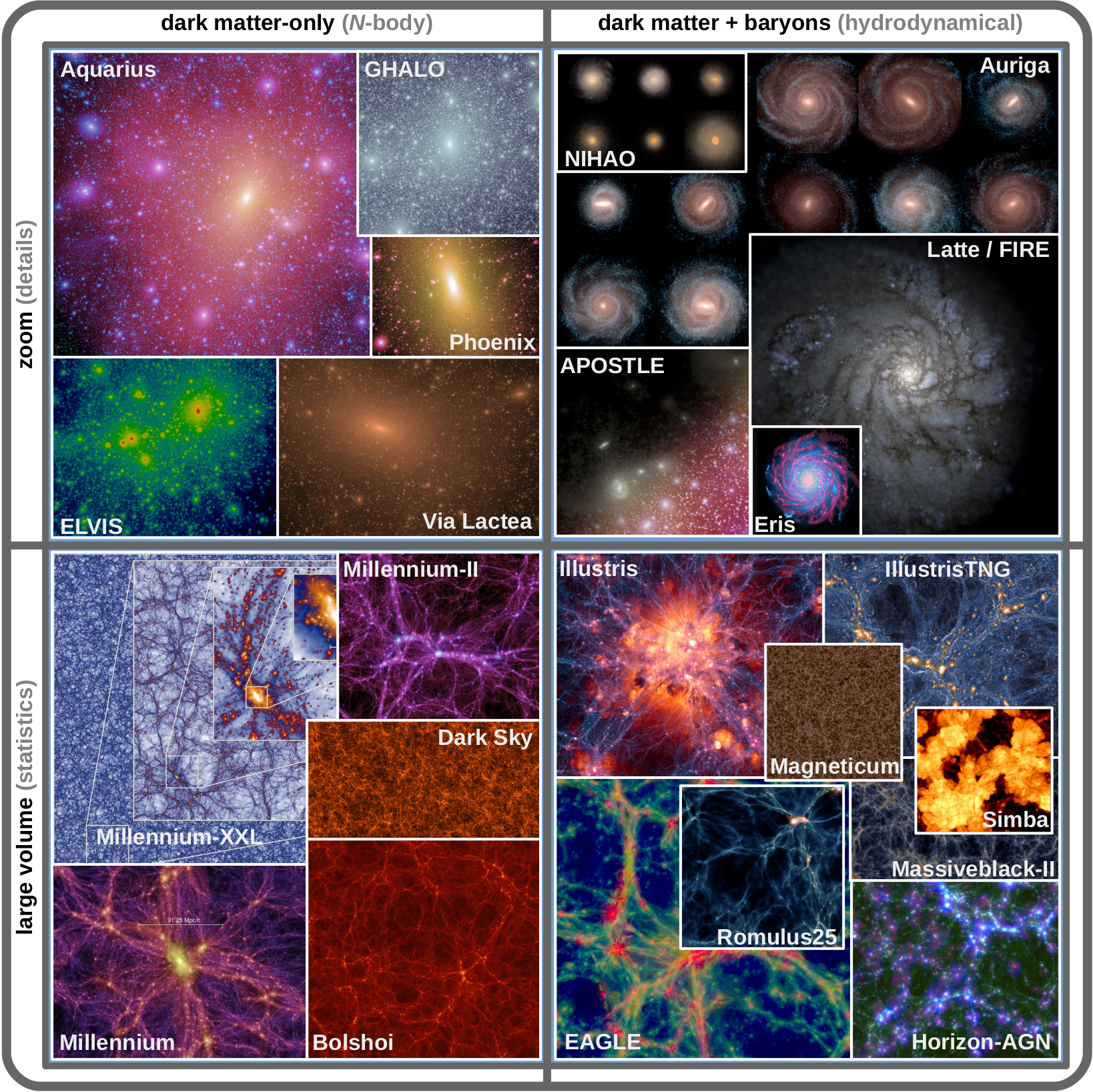

The study of the formation of large structures in the nonlinear regime using N-body simulations (dark matter) and hydrodynamical simulations (including baryonic physics) has led to tremendous advances in our understanding of the cosmic web and galaxy populations, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3:Slices of simulations of the cosmic web and of zoomed-in regions (dedicated simulations) in a framework. Extracted from Vogelsberger et al. (2020).

It should be noted that simulations on small and intermediate scales (kpc-Mpc) have historically encountered a number of difficulties. These include:

- The core-cusp problem: the simulated dark matter density profiles appear too pointy compared to what can be inferred from kinematic observations. The likely solution to this problem lies in outflows in the vicinity of supermassive black holes (jets, winds) or in central regions of high star formation (collective winds from stellar explosions);

- The number of satellites of giant galaxies: the simulations tend to produce too many (100-1000) dwarf satellite galaxies compared to the hundred or so observed around the Milky Way at masses above . The solution to this problem probably lies in the lower efficiency of galaxy formation at the lower masses of dark matter halos.

- Size of the largest satellites: Simulated halos of satellite galaxies tend to be larger than those of the largest galaxies orbiting the Milky Way and Andromeda. The likely solution to this problem lies in tidal stripping effects on baryons.

In all three cases, the inclusion of feedback from outflows and tidal effects appears to be crucial for the agreement between simulations and observations.

2Dark-matter candidates and beyond-standard model physics¶

The two main properties inferred for dark matter are

- Cold: a low bulk/rms velocity, i.e. and , so that dark matter does not escape from the Milky Way halo.

- Dark: while being coupled to the gravitational sector, dark matter should be weakly coupled to the particles of the Standard Model. Otherwise we would see dark matter e.g. through its electromagnetic emission. This darkness suggests candidates with no electric charge or colour, and a lifetime longer than the age of the Universe.

The three main candidates put forward that appear to meet these criteria are discussed below.

Wave dark matter candidates¶

The first quantity to consider for a candidate of wave nature is its de Broglie wavelength:

with velocity , e.g. . Consider a wave that extends at most on the kpc scale to keep the packet sufficiently concentrated in the centre of the galaxies, i.e. . This condition imposes a minimum mass on the candidate:

On the opposite end of the mass range, one can use the local energy density of to set the maximum mass a wave dark-matter candidate. Such a candidate would have to be bosonic in nature and a sufficient number of particles would have to occupy a cell for a condensate to form, i.e. . With a bit of algebra, one finds

Wave dark-matter candidates are therefore searched for in a broad mass range covering . The most promising candidates from particle physics are the axions, which remain unobserved to date. These hypothetical particles have been invoked to solve the strong CP problem in quantum chromodynamics, i.e. the fact that the electric dipole moment of neutrons is observed to be times weaker than expected from the Standard Model.

Axions from quantum chromodynamics exhibit a mass-dependent coupling to photons, . More generally, axion-like particles are searched for in the whole parameter space . Gamma-ray astronomy at GeV-TeV energies currently places the strongest constraints on the coupling of axion-like particles to the electromagnetic sector for masses in the neV energy range. The mass range that remains open for axions to explain dark matter goes up to while the entire mass range remain open for axion_like particles.

Particle dark matter candidates¶

Weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) with decouple (“freeze out”) at the right time, , to produce today’s relic abundance. This is the so-called WIMP miracle, which is seriously put to the test by recent measurements around .

The relic abundance depends on the annihilation cross section, σ, or on the decay time in one or more channels that are hopefully linked to the Standard Model. The equation that governs the evolution of the comoving density of the number of dark matter particles, , is , with the scale factor, i.e.

where .

With losses due to annihilation, the equation becomes

where is a constant such that without loss term .

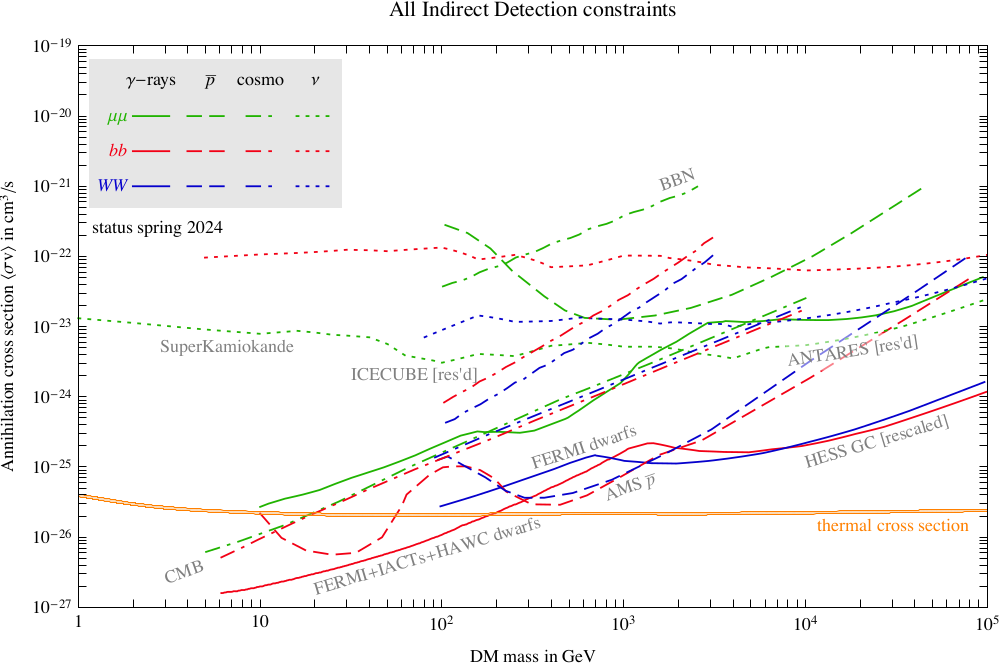

Freeze-out occurs for i.e. for . The thermal averaged annihilation cross section, such as , is . As illustrated in Figure 4, annihilation of WIMPs in the channel has been ruled out for masses up to by Fermi-LAT observations of dwarf galaxies, where little gamma-ray emission from astrophysical sources is expected. The mass range remains open at higher energies. This channel is expected to be probed down to the thermal cross section for masses up to with the Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory (CTAO). CTAO observations should then either close the mass range usually inferred for WIMP dark matter (if dark decays through the channel) or discover its signature.

Figure 4:Upper limits on the annihilation cross section of WIMPs as a function of the mass the dark matter candidate. The thermal cross section is shown in yellow. Extracted from Cirelli et al. (2024).

Macroscopic dark matter candidates¶

Let’s conclude this overview with the macroscopic dark matter candidates. A wide range of masses have been ruled out by lensing studies, namely masses greater than , i.e. heavier than large asteroids. At lower masses, the remaining viable candidates are primordial black holes, formed not by the collapse of stars but by that of initial overdensities, for example during the radiation era.

Such small black holes are expected to emit a blackbody spectrum with a temperature of (Hawking (1974)):

The energy loss rate then follows the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

where is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant and where with the Schwarzschild radius.

This yields

where

that is a timescale comparable to the age of the universe for an initial mass . Such an initial mass yields an initial black-body temperature which should increase as the primordial black hole evaporates.

We therefore expect Standard Model particles with energy/mass to be emitted during the final stages of the evaporation of the primordial black hole. Searching for the time signature of such events through their emission of cosmic rays, gamma rays and neutrinos has ruled out the possibility that primordial black holes of less than make up 100% of the dark matter.

The mass range between and remains open for macroscopic dark matter.

Other searches beyond the standard model¶

A last type of search for physics beyond the Standard Model using astroparticles is worth mentioning here, although it does not involve dark matter. Because of their high energies and the large distances they travel, astroparticles are remarkable probes of the violation of Lorentz invariance. The reference energy at which such violations might be expected, in theories attempting to unify gravity with the other fundamental forces, is Planck’s energy, . The Planck energy may seem far from the energies reached by astrophysical sources (let alone by humans), but the distance helps...

The observational constraints are most often placed on corrective terms (Taylor expansion like) to the dispersion relation that is expected in effective field theories:

where is the four momentum of the particle of interest, its mass, the energy of the violation (presumably close to the Planck scale) and the order of the modification. The sign ± indicates that both signs are considered for the modification, with the sign corresponding to a so-called superluminal term and the sign to a subluminal term.

Note that corrective terms with an even order (e.g. for quadratic term) emerge from operators that are invariant under charge/parity/time-reversal (CPT) symmetries, although the CPT symmetry could be violated at energies close to the Planck scale.

Two types of signatures emerging from the corrective term are searched: a temporal signal and a spectral signature. The search for such effects requires the use of the most variable and most energetic extragalactic sources, namely jetted active galactic nuclei and gamma-ray bursts. The best constraints using both channels and the types of sources nowadays exclude a linear modification of the dispersion relation up to a few times the Planck scale.

Temporal signature of Lorentz invariance violation¶

The energy-dependent time signature can be understood using the mechanical Hamiltonian . By differentiating Equation (11), we get

that is

as for the energies relevant to astroparticles. This equation justifies the use of the term super/subluminal for the positive/negative corrective term in Equation (11).

The difference in arrival time between two photons of energies and emitted at the same time by a source located at a light-travel distance is thus:

where we have neglected the redshift dependence.

For a subluminal linear modification of the dispersion relation of gamma-rays, if and for a source located at , one gets

This corresponds to the observed short timescale variability e.g. of gamma-ray bursts, enabling to place stringent

lower limits on for a linear modification.

Spectral signature of Lorentz invariance violation¶

The second signature is based on the modification of the pair-production threshold, for gamma-rays traveling over cosmic distances and interacting with photons of the cosmic infrared background.

A subluminal modification of the dispersion relation of photons, of energy (assuming that the electrons are not affected for the sake of simplicity) yields a modification of the infrared photon threshold energy as (Jacob & Piran (2008)):

where

This is precisely the energy up to which γ-rays at distances around have been observed, enabling to place stringent lower limits on for a linear modification. Although a linear modification of the dispersion relation is now ruled out up to the Planck scale, the energy range beyond remains open for the quadratic subluminal term, which arises from an operator invariant by CPT symmetry.

- Driver, S. (2021). The challenge of measuring and mapping the missing baryons. Nature Astronomy, 5, 852–854. 10.1038/s41550-021-01441-w

- Jiao, Y., Hammer, F., Wang, H., Wang, J., Amram, P., Chemin, L., & Yang, Y. (2023). Detection of the Keplerian decline in the Milky Way rotation curve. \aap, 678, A208. 10.1051/0004-6361/202347513

- Hunt, J. A. S., & Vasiliev, E. (2025). Milky Way dynamics in light of Gaia. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2501.04075. 10.48550/arXiv.2501.04075

- Licquia, T. C., & Newman, J. A. (2015). Improved Estimates of the Milky Way’s Stellar Mass and Star Formation Rate from Hierarchical Bayesian Meta-Analysis. \apj, 806(1), 96. 10.1088/0004-637X/806/1/96

- Evans, N. W., O’Hare, C. A. J., & McCabe, C. (2018). SHM++: A Refinement of the Standard Halo Model for Dark Matter Searches in Light of the Gaia Sausage. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:1810.11468. 10.48550/arXiv.1810.11468

- Gonzalez, A. H., Sivanandam, S., Zabludoff, A. I., & Zaritsky, D. (2013). Galaxy Cluster Baryon Fractions Revisited. \apj, 778(1), 14. 10.1088/0004-637X/778/1/14

- Planck Collaboration, Aghanim, N., Akrami, Y., Ashdown, M., Aumont, J., Baccigalupi, C., Ballardini, M., Banday, A. J., Barreiro, R. B., Bartolo, N., Basak, S., Battye, R., Benabed, K., Bernard, J.-P., Bersanelli, M., Bielewicz, P., Bock, J. J., Bond, J. R., Borrill, J., … Zonca, A. (2020). Planck 2018 results - VI. Cosmological parameters. A&A, 641, A6. 10.1051/0004-6361/201833910

- Vogelsberger, M., Marinacci, F., Torrey, P., & Puchwein, E. (2020). Cosmological simulations of galaxy formation. Nature Reviews Physics, 2(1), 42–66. 10.1038/s42254-019-0127-2

- Cirelli, M., Strumia, A., & Zupan, J. (2024). Dark Matter. arXiv E-Prints, arXiv:2406.01705. 10.48550/arXiv.2406.01705

- Hawking, S. W. (1974). Black hole explosions? \nat, 248(5443), 30–31. 10.1038/248030a0

- Jacob, U., & Piran, T. (2008). Inspecting absorption in the spectra of extra-galactic gamma-ray sources for insight into Lorentz invariance violation. \prd, 78(12), 124010. 10.1103/PhysRevD.78.124010